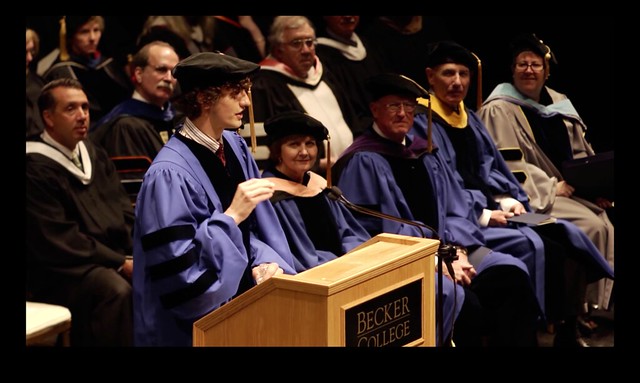

Worcester, MA: Becker College, May 14, 2012.

Candidates for the Class of 2012, it is a distinct honor for me to address you all today. I grew up not far from here in a little town called Lynnfield just north of Boston, so this is very much home to me and your welcome means a great deal.

Ever since I was invited, I’ve been wondering how this will go. Honestly, I’ve never given a speech like this before. I’ve even had a few stress dreams about it. You know like those dreams where it’s the day of the final and you haven’t studied all semester? Those dreams.

Then I woke up today, and I realized something very important: I’m going to give this speech, and of all the things I say to you now, most likely you’ll remember only that I was here. If you laugh five times in the next fifteen minutes, you’ll remember that I was kind of funny, and that’s it.

So, take a moment to remember and describe how you feel. Find a few words for this New England weather. Because honestly that is all I remember from Swarthmore College graduation day. I felt optimistic while Michael Dukakis spoke, then it rained on us. End of story. I don’t even remember who spoke at Harvard when I got my Masters. It was sunny, someone spoke for a while in Latin, and my Dad was there… that’s all I got. So I’m gonna keep this brief.

I see all graduates like little startups. You start out with almost nothing, just an idea of what you want to be when you grow up. Likewise, when you start a business you never really know what it will eventually become. That was definitely the case with Odeo, the company that gave birth to Twitter.

A good startup is full of life and energy, optimism and hope, just like the undergrad. The strongest asset of the new graduate is the loyalty and friendship of their institution, their social network. Every startup I’ve witnessed trades in that exact commodity, and most of them grow out of relationships created in college or graduate school.

I judge a startup by its bicycles; similarly I don’t know many new graduates with their own car. So please indulge me as I replace the word “graduate” with the word “startup” and provide a few lessons from business and real life starting from scratch.

In real life, it’s so important to be nice to the small people. Make friends with security, say hello to housekeeping, appreciate the admins, get to know people on the front lines of whatever company you join. I believe that the lowest of us inevitably rise up. Let me just tell you how I know this from first-hand experience.

In 2005 I worked at this podcasting startup called Odeo. I was the Head of Quality, which basically meant I got to break things before the user did. I’m really good at breaking things. Actually, I believe that breaking things quickly is a path to learning.

The Odeo service was great, you could podcast from anywhere, even from your phone. But we were working completely from Open Source. In fact, I used to say that we were building Beta products using Alpha tools. The entire system was very fragile, and only the bravest engineers dared to join us.

One of these super-bold super-nerds signed up as an intern, for like no pay. Jack taught him JavaScript that Summer, and he stayed long enough to internalize our core beliefs: Simplicity, Constraint, and Craftsmanship.

As we struggled to gain users with Odeo, our intern left to create his own thing. That young man’s name is Kevin Systrom. Does that ring a bell? Kevin recently sold an insanely popular app called Instagram to Facebook for a cool one billion dollars. Why is Instagram so successful? It is a photo-sharing service built entirely upon simplicity and the constraint of the square pane.

This brings me to my first point: simplicity is its own reward. There were plenty of photo-sharing services out there when Instagram hit. Most of them did more than Instagram does, but none of them did fewer things, or better. Kevin found the absolute minimum viable product, and made it the best it could be.

Simplicity makes your concept easier to create, to maintain, and ultimately makes the idea easier to describe and later to sell.

Simplicity is also Twitter’s main feature. What our team did was to reduce the number of steps from impulse to action. The day we discovered the idea, Jack and I were a couple of engineers at Odeo, given a full day to harvest all of our best ideas for something we called a Hackathon. We were trying to save our little company from extinction, and as we sat atop a children’s slide in South Park, San Francisco, Jack said to me, “I want to make something so simple, you don’t even think about it, you just write.”

Arguably people DON’T think about what they write, which gets some folks into trouble. So here is a nickel’s worth of free advice: what not to do.

Don’t drink and tweet. Or as Jack once wrote: “Some things CAN’T be said in 140 characters, especially after champagne.”

Here’s another thing I’ve learned: Don’t go for the big money right away. Watch out for the fat job, beware of too much comfort because it’s almost impossible to go back to the lean lifestyle, by choice. To the entrepreneurs in the audience, I’ll make this even more plain: Don’t take venture capital.

It is entirely possible to bootstrap your idea. It takes longer, but you will own more of it and no one can tell you what to do with it. Twitter was personally incubated for over a year by the executives before it spun off into its own company. Why did they do this? Because they understood that being ahead of your time only means bad timing.

This reminds me of the principle lesson of bootstrapping, and it’s easy to say but truly difficult to live by: Don’t spend money. As our grandfather always said, “Invest in yourself first.” Another commonality among Twitter, Instagram, Square, and Facebook was the incredibly small early teams.

Bootstrapping provides constraint, and this brings me to my second major point of today: embrace constraints. Twitter has the obvious constraints of 140 characters, immutability, and asymmetrical relationships. Apple is a company that operates on the principle of small teams that always seem to have a little bit less than they need to get the job done. But somehow it gets done. This is because constraints enable creativity.

What does Scotty always tell Kirk in the middle of the battle, when all hell is breaking loose? “I canna do it, Captain—I need more time!!” But what always happens? He fixes the trilithium chamber, or the warp coils, or the phasers at the last second anyway.

Why is this story compelling, over and over again? Because fundamentally the best of us believe in the most basic element of success: the constraint of time.

Every major accomplishment in my life was completed in under one month. Once we vetted the idea, chose the team, and produced the original design, the actual working code for Twitter was produced in only a few weeks. A year later, my friends and I organized the first iPhone Developers Camp in 21 days from first tweet to first seat.

The camp event is structured entirely around constraints. Yes, we give participants unlimited food, coffee, water, wifi, power strips, and access to the community. But you have to produce everything within the 48 hour weekend, and you only get 4 minutes to present during the Hackathon Contest.

The stuff that people create this way is astounding. I’ll name just a few of the companies that alums have built. Tapulous, bought by Disney. PhoneGap, sold to Adobe. Small Society, sold to Walmart Labs. Chaotic Moon, creators of The Daily, and a ton of other apps that you use every day. Yes, even Square was started by camp alums Jack Dorsey and Tristan O’Tierney.

Why does this formula work? I believe it’s because constraints also inspire trust, and here’s an example. One year after the first iPhoneDevCamp, a select group of camp alumni delivered the Official Obama ’08 iPhone app in 22 days, from concept to App Store download.

Our major constraint was something the government calls “Top Secret”. No one outside of the team and our significant others knew what we were doing. Therefore we had zero distraction. That app achieved over half a million downloads, which represented a very large percentage of app users at the time.

I embrace this belief so fully that the following year, I formed an entire company based on a few simple constraints. My company DollarApp is simply a filter for ideas. What we do is we ask ourselves: what is the one thing about this app that works better than anything else? What is this app the best at doing? Then we boil that feature down so that it can be produced by one person in just one month.

If we’ve really done that one thing in one month with just one person, then I feel confident charging one dollar for the download. You don’t HAVE to ship it, but the DollarApp philosophy gives you the choice. This limits risk, exposure, and overhead. You can see this principle at work if you’ve got iPhone or iPad, just search for “Big Words”. Go ahead, I’ll give you a sec.

Ok, so you understand simplicity and constraint. I like to think in threes, it’s something that keeps me centered. So the third core belief I hold is called Craftsmanship. To me this means something very basic: only build something that you yourself need to have in this world. We needed Twitter to communicate as a team. We needed it to be simple, and reliable, and beautiful. If it broke, we would rush to fix it. When Twitter goes down, it feels like baby pandas crying. It’s the worst!

I needed Big Words to be an example of what I could do by myself. Craftsmanship is caring, and obsessing over every detail. This idea brings me to the third and final message I have for you today.

One word: focus. Concentration is a startup’s most valuable commodity. Lose focus for one moment and you’re dead. Take advantage of your ability to go all night and use it to focus.

Why did Odeo ultimately fail? We had exactly one podcaster in our podcasting company: me, the test engineer. I was the only one of us really using the product on a daily basis! No wonder we pivoted to focus on Twitter.

Focus, and don’t give up. Success is saying “no” a thousand times, then saying “yes” only once. Now you may be saying, “Dom, I’m no software engineer, none of this stuff matters to me.” If you are into nursing, or animal studies, or even if you were an English major like me, you can still build something very important.

Manufacture your own personal brand. Discover what you are the best at doing, and market that. This is your public image. Sculpt it, hone it, fit it into one sentence and practice the elevator pitch for your brain.

Get there by continuously asking yourself one question: Why? Why do I love doing this? Why is this so important to me? Why should anyone care what I am good at doing? The answers to those questions will expose your own core beliefs.

Focus on what you love to do, even if that thing doesn’t pay well right away. I love to write, but writing doesn’t pay very well—at all. So right out of college I took an engineering job in Silicon Valley, and started taking notes. A decade of notes and quotes, plus three years of waiting for the right moment, and it took just one month of thousand-word days to complete my book. That, my friends, is what I mean by focus.

I believe you can start with nothing but laser-tight focus, and glory will eventually be yours. I believe that we spend our lives accumulating choices, and the best of us filter them by choosing the right constraints. I believe that proper constraints lead to the simplest solution, and I truly believe that anyone is capable of success as long as you define success for yourself.

Ok, so what’s the message today? Um, don’t tweet and drive, um, ahhh, learn to live off of ramen, and ahhh, um, something about concentration. No seriously, here’s what I’d like you all to remember:

1. Simplicity is its own reward,

2. Embrace constraints, and

3. Stay focused on what you love to do, what you are best at doing. Focus by saying “no, no, no, no,” and then, “yes”.

Everyone wants to change the world for the better, overnight. And that’s okay, that’s good. It’s fine to dream of a better world. Cherish your dream, nurture it. Never, ever, EVER give up on your dream.

Yes, dream big. But start small.

Thank you.

—